Walking down the streets of Lancaster city can give you the feeling that you’re traveling through time. The buildings you walk past aren’t just offices, stores, and homes; they’re witnesses to revolution, industrialization, and the lives of the people who came before us. Lancaster’s architecture is a living history; each block is a chapter in the city’s story.

A German Foundation

The story begins in 1719, when Hans Herr and his family built their house in (what would become) Lancaster County. The home is the oldest structure in Lancaster County and reflects construction techniques from Hans Herr’s homeland: steeply pitched roofs, central chimneys, and thick stone walls.

By the 1730’s, when the town of Lancaster was officially founded, Germanic influence was evident throughout the landscape. The original town took shape around a courthouse on Penn Square that was completed in 1738.

That courthouse is long gone, destroyed by a fire in 1784, but the square remains, and is still the city’s hub almost 300 years later.

The Rise of Georgian Elegance

As Lancaster grew into a proper city, a new architectural style emerged. Georgian architecture brought symmetry, balanced proportions, and classical motifs. One of the best remaining examples of this style is the red brick, Georgian-style Trinity Lutheran Church. Work on the church began in 1766 and was completed in 1794. When its 195-foot steeple went up, it became the tallest building west of Philadelphia.

Lancaster’s most prominent figures of the time also implemented the style in their homes. Pennsylvania Chief Justice Jasper Yeates commissioned a 3-story brick Georgian home on South Queen Street for his son-in-law. General Edward Hand, George Washington’s adjutant general, built his home, Rockford, in the Georgian style overlooking the Conestoga.

A Federal Revolution

In 1777, the Continental Congress, while fleeing Philadelphia, met in Lancaster’s courthouse. Lancaster was the capital of the United States for one day.

After the American Revolution, the Federal style emerged in Lancaster, bringing delicate ornamentation, arched windows and doorways, and refined proportions.

According to John J. Snyder Jr. in his 1998 report on the Montgomery House:

“The Federal style favored ornament derived from ancient Roman architecture, including classical figures, delicate leafage, swags, garlands, beaded borders, and friezes of reeding. Notably, there was a preference for circular, oval, and elliptical forms. These forms found numerous and diverse expressions: fanlights over doorways or as separate windows; dramatic, curving stairways with continuous handrails; rooms of oval or apsidal-ended form; and oval or fan-shaped decorative devices.”

William Montgomery’s restored brick Federal-style home on South Queen Street, designed by Stephen Hills in 1804, exemplifies the new American aesthetic.

The Victorian Boom

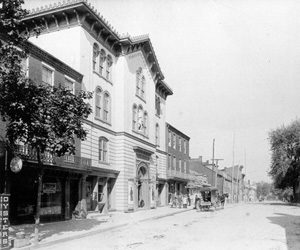

In the mid-19th century, Lancaster exploded. The city tripled in size. Factories rose. Railroads connected Lancaster to the world. Manufacturing brought wealth, and wealth demanded expression. The result was an architectural revolution that gave Lancaster its prevailing character.

The Fulton Opera House, completed in 1852 in a Victorian style, became a center for performing arts and civic affairs. A prominent statue of Robert Fulton, the Lancaster native and steamboat inventor, stands as a reminder of the inventors and innovators that Lancaster has produced.

But the real story of Victorian Lancaster is written in the red brick and dark mortar, in ornamental friezes and elaborate patterns, in turrets and towers and gambrel roofs that adorn many homes throughout the city. The Queen Anne style took hold with a vengeance.

The Southern Market, built in 1888, signaled the arrival of a new type of building: structures that celebrated complexity and industrial confidence.

The Urban Era

In 1886, a 23-year-old named Cassius Emlen Urban returned to Lancaster, arriving at just the right time. Lancaster was booming, and the city needed architects who could translate industrial prosperity into stylized architectural form.

Urban’s first major project came at age 25: the Southern Market. The Romanesque Revival building, with its ornate brick and stonework and distinctive checkerboard pattern, launched one of the most prolific architectural careers in American history. Over the next 45 years, Urban would design more than 100 buildings that still define Lancaster’s skyline.

When you walk through downtown Lancaster today, you’re walking through Urban’s imagination. Central Market, with its Romanesque Revival arches. Lancaster City Hall, with its Venetian Renaissance influences. The Fulton Opera House facade, which Urban updated in 1904 to modernize it for the 20th century.

In 1925, at age 62, Urban designed his masterpiece: the 14-story Griest Building in Italian Renaissance Revival style.

The Twentieth Century and Beyond

Lancaster’s architectural story didn’t end with Urban’s retirement in 1930. The city continued to evolve.

One of the best examples is the Ware Center, the last building designed by the renowned architect Philip Johnson. The structure is characterized by the juxtaposition of glass and stone, and features refined, clean lines typical of Johnson’s later, functional style. The contrast between Johnson’s modernism and the Victorian streetscape around it shouldn’t work, but somehow it does. Like the Georgian mansions alongside the Germanic homes, it’s another layer in Lancaster’s urban landscape.

Today, Lancaster’s National Register Historic District covers approximately three square miles and contains more than 13,000 buildings, making it one of the largest urban historic districts in the United States. Most of the structures are from the 19th century, giving the city a predominantly Victorian character, but as we’ve already discussed, a diverse range of architectural styles are on display throughout the city.

Walking Through Centuries

Lancaster is one of the few places where you can walk from the 1700s to the 2000s, observing 34 architectural styles, in the span of a few blocks. Georgian townhouses stand next to Queen Anne mansions. Federal homes face Romanesque Revival markets. Colonial Revival churches neighbor Moorish Revival city halls.

Lancaster’s architecture is a conversation across centuries, each generation adding its voice without drowning out what came before. The next time you have a chance to spend some time in Lancaster city, take a minute to appreciate the details of the structures that line our streets. The buildings anchor us to our past and should inspire our future.

They remind us that we’re not the first to walk these streets, and we won’t be the last.